Ecojustice’s new Climate Change director on the moment that transformed his understanding of climate change — and how that’s shaping his vision for Ecojustice’s future work.

I was partway through my first year of living in Vancouver when wildfires broke out across British Columbia.

For weeks, the smoke from nearby forest fires rolled into the city, spurring the longest air quality advisory in the region’s history. The air turned an eerie shade of orange. When I stepped outside, I could taste the acrid smoke and feel it catch in my throat. The great outdoors I had moved here to enjoy were temporarily off limits.

This was the first time climate change really hit home for me.

How I got here

Don’t get me wrong: I already knew that climate change is one of the most monumental problems we face. In fact, I’ve been worrying about climate change since I was about 10.

I was born in Canada, but moved to the U.K. when I was very young.

Growing up in England in the 1990s, climate change was one of the main environmental issues I learned about at school. But it always felt like a distant threat, something very bad that could happen in the future, mainly to people in other countries, and even then only if we were stupid enough not to take action.

Years later, I became an environmental lawyer and stopping climate change became part of my job. For 10 years, I led the clean air team at ClientEarth, a U.K.-based environmental law non-profit much like Ecojustice. I won a number of high-profile cases with ClientEarth, including one that went all the way to the European Court of Justice, setting a precedent that established that EU citizens have the right to breathe clean air.

By 2017, however, I was ready for a new challenge. I packed up my London flat and relocated to Vancouver, drawn by the nearby mountains and opportunity to join Ecojustice’s groundbreaking work.

Eight months later, B.C.’s wildfire season was in full swing.

A new reality

Having lived in London – a city infamous for its “pea souper” smog, I’m no stranger to poor air quality. My career has even taken me to places such as Hanoi and Delhi, which are among the world’s most polluted cities.

But the pollution in Vancouver last summer was the worst I’ve ever experienced. Watching wildfires rip through my new country made climate change real, immediate and frightening.

B.C.’s 2018 forest fires were the worst the province has ever seen. But the previous record was only set a year earlier. A government report called it the “new normal,” and said we can expect more intense and more frequent fires as the climate becomes warmer and drier.

A few months after the air quality advisory ended in B.C., The Lancet — one of the world’s leading medical journals — released a report that called climate change the biggest global health threat of the 21st century.

Whether you’re in Hanoi or Delhi, London, or Vancouver, these threats to human health are unacceptable. And if we want to address them, we must summon the courage to take bold action now.

Charting a path forward for Ecojustice’s climate work

As we enter 2019 and work to recalibrate Ecojustice’s climate strategy, I keep returning to three central ideas. These are what I’d like to leave you with today:

One: Climate change is real.

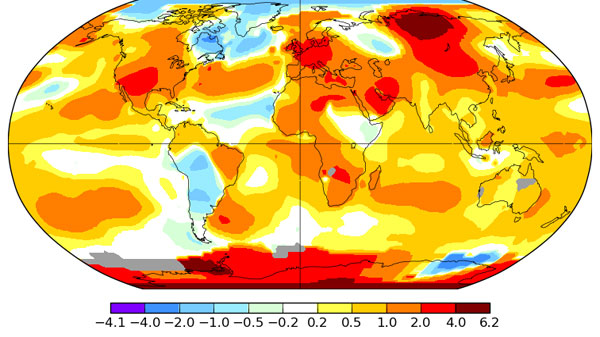

The scientific consensus on climate change is overwhelming. According to a 2016 study, 97 per cent of the world’s publishing climate scientists agree that climate change is real and that humans are to blame.

To put this in context, Kate Marvel, a scientist at NASA, said, “We are more sure that greenhouse gas is causing climate change than we are that smoking causes cancer.”

Two: Climate change threatens human health, security and wellbeing.

In a landmark report released in October, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned that if global warming exceeds 1.5 degrees Celsius — the threshold set out in 2015’s Paris Agreement — the world will experience more extreme temperatures, more melting sea ice and sea level rise, and more threats to our food security, water supplies and safety.

And the people who will suffer the brunt of these impacts will be the most vulnerable among us — the poor, the elderly, and the very young.

Three: We have 12 years to address climate change

The IPCC report was clear: The next 12 years are critical if we want to keep warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius and avoid climate disaster.

To do this, we’ll need to set ambitious emissions targets and stick to them.

Globally, we must halve our carbon pollution by 2030 and get to zero emissions by 2050. In Canada, this cannot happen without creating and enforcing laws that ensure a safe climate for future generations.

The challenge is huge and the stakes couldn’t be higher, but I am committed to using the power of the law to set Canada on the path to a safe climate — and I will not be going it alone. I’m honoured to work with such dedicated and courageous lawyers, scientists, staff and supporters like you who power Ecojustice.

Thank you for welcoming me to the Ecojustice community, and for supporting the vital work this organization does and our bold vision for a climate-safe future protected by strong, enforceable laws.

Now, let’s get started.