Alberta’s tar sands is the most destructive oil operation in the world, obliterating the land on such a mind-boggling scale that it can only be fully appreciated from space. When the devastation is that huge, it’s easy for it to become abstract and blot out any individual’s suffering.

But the fall-out from Canada’s oil sands project has a real human cost — just ask Chief Allan Adam of Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation. His is the closest community downstream from the Athabasca oil sands, where decades of exposure to industrial waste have left people sick and dying young. “It’s no surprise that we live with the highest cancer rates in the province,” says Chief Adam. “Over twice that of the rest of Alberta.”

What are tar sands and why are they a problem?

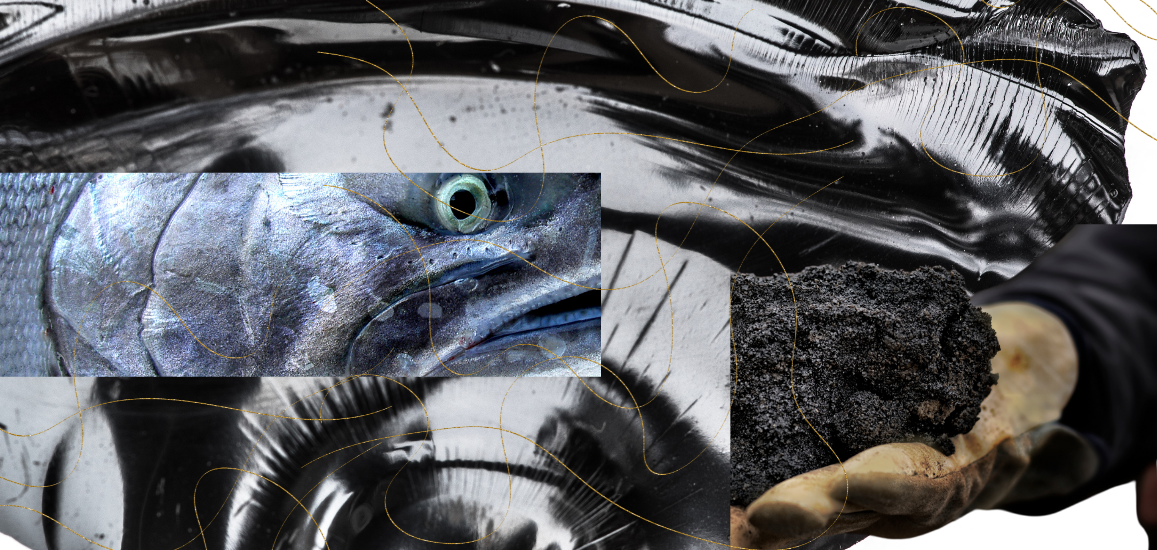

Tar sands (or as the petroleum industry savvily rebranded it, ‘oil sands’) are a mixture of sand, clay, water, and a thick, foul-smelling substance called bitumen. It takes an awful lot of work to squeeze anything resembling a usable fuel from this mess, and the waste material left over from the extraction process winds up in manmade pools called tailings ponds.

In John Vaillant’s recent blockbuster book Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World, which looks at the devastating 2016 fire in Fort McMurray, the author describes the bitumen refinement process. He writes that to turn this noxious sludge into a marketable fuel, “the bitumen industry uses more than 2 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day (the energy equivalent of 350,000 barrels of oil), for the sole purpose of separating bitumen from sand.”

It is the most greenhouse gas-intensive petroleum product in existence.

The world’s dirtiest oil also comes with harmful leftovers. Vaillant points out, “There is no place for this toxic sludge to go except into the soil, or the air, or, if one of the massive earthen dams should fail, into the Athabasca River.”

Last year, a tailings spill at Imperial Oil’s Kearl mine leaked 5.3 million litres of toxic wastewater into the surrounding environment, causing untold damage to people and nature.

What are the toxic chemicals in tailings ponds?

One dangerous component of oil sands tailings is something called naphthenic acids, which is known to kill birds, fish, and, rather specifically, impair the reproduction of wood frogs.

Back in 2008, the death of 1,600 ducks made headlines across Canada. The birds died after landing on a tailings pond north of Fort McMurray — an alarming event captured in Kate Beaton’s bestselling autobiographical comic Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands. Incidentally, Ecojustice helped secure a legal victory against Syncrude, the oil company responsible.

As for the impact on human health, what readers of Beaton’s memoir might not realise is that many of the oil sands workers featured in the book have since died of cancer — including the author’s sister.

Chief Adam notes, “the cancerous effects of naphthenic acids have long been known to scientists, industry, governments, and sadly, to our community of Fort Chipewyan.”

A new tool under the revised Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA)

Earlier this year, Ecojustice — on behalf of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, Environmental Defence and Keepers of the Water — was able to use a new tool under the recently revised Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA) to request a long-awaited investigation into naphthenic acids.

“Naphthenic acids from tailings ponds have been found in surface water and groundwater in the Athabasca oil sands region,” explains Ecojustice lawyer Bronwyn Roe. “The harms that these chemicals cause to people and the environment need to be better understood, and naphthenic acids need to be regulated to prevent harmful exposure.”

“For years, Indigenous Peoples in the oil sands region have called on the government to assess naphthenic acids,” says Roe.

On May 30, the federal ministers of environment and health agreed to assess whether naphthenic acids are toxic under CEPA — this is a huge first step. And it only happened because we were able to use a piece of legal weaponry from the modernised CEPA. More than 31,000 Ecojustice supporters and a coalition of environmental groups were instrumental in securing these much-needed updates to Canada’s cornerstone environmental law.

Let’s pause for a second. Just as zooming out gives us a better picture of the planetary scar that is the Alberta tar sands, stepping back lets us see how so much of Ecojustice’s work is connected.

What else has the new CEPA allowed Ecojustice to do?

As promised, here come the dead salmon. In February, Ecojustice submitted a formal request to the federal government on behalf of Raincoast Conservation Foundation, Watershed Watch Salmon Society, and Pacific Salmon Foundation. Under the power of a revamped CEPA, we asked the Feds to prioritize the tire chemical 6PPD for assessment. 6PPD is a chemical linked to mass die-offs of coho salmon.

To get nerdy for a second, this was the first time the Section 76 amendment to the CEPA legislation was used to successfully request prioritization. It was also the first time Canada has taken action to address 6PPD, something which the States is far further along.

“Everything is connected.”

At the end of May when news broke that Ministers Guilbeault and Holland had agreed to assess the toxicity of naphthenic acids, it was an important step — both towards reconciliation and to regulating these cancerous compounds.

In the words of Jesse Cardinal, executive director for the nonprofit organization Keepers of the Water, “We’re the first scientists of this land, and we understand how everything is connected.”

“For several generations, we have been the first witnesses and the first affected by the devastating impacts of these intensely toxic so-called development projects on a once richly diverse wildlife, landscape and waterway system.”

Cardinal’s talking about the tar sands, of course, and the naphthenic acids assessment, but what she’s describing is environmental racism against Indigenous communities. Even now, Senate is dragging its feet on passing Bill C-226, a piece of legislature which would begin tackling environmental racism in Canada.

And as we’ve learned from CEPA, real change takes countless hours of dedication from untold number of people, across years and even decades. Ecojustice won’t give up, because for impacted communities such as the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, giving up isn’t an option.