Update: On September 23, 2020, the federal government announced its new legislative agenda in the Speech from the Throne. In the speech, the federal government committed to immediately bring forward a plan to exceed Canada’s 2030 greenhouse gas goal and legislate net-zero by 2050.

However, Canada has missed every emissions target it has ever set. That is why we need a new climate law that includes mechanisms that will hold this, and future federal governments, to account for its commitments to reduce Canada’s emissions and achieve our climate targets.

Provinces and municipalities across Canada are carefully reopening the country in phases after COVID-19-related shut-downs. And increasingly, Canadians are looking with curiosity and trepidation to what the world will look like post-pandemic.

Increased levels of stress and anxiety, fuelled by the pandemic and social isolation, have left Canadians feeling uncertain about the future. But even before the pandemic emerged, Canadians were also feeling the stress of our changing climate – a rising number of Canadians have reported eco-anxiety.

Global emissions continue to rise against a backdrop of wildfires, dangerous flooding and an increased threat to food security – all while the science sounds alarm-bells. The IPCC warn that the world has just ten years to act to avert irreversible climate change.

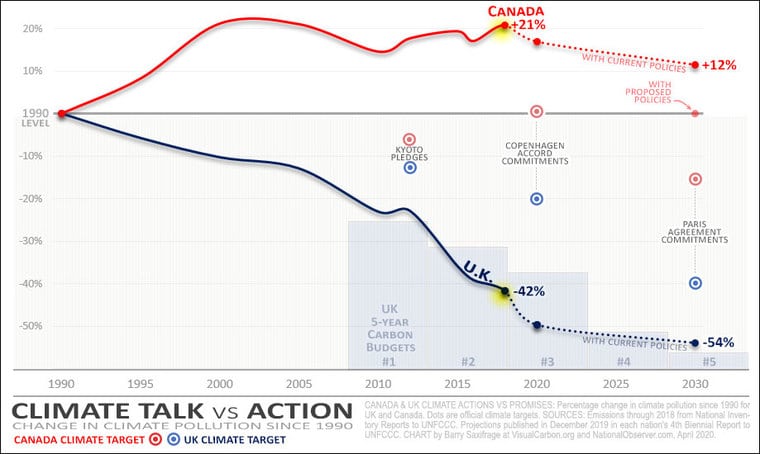

Canada has missed every GHG target it has ever set. In 1997’s Kyoto Accord, Canada promised to lower its emissions to 576 Mt by 2012. We missed that target by 25 per cent. In 2009, in Copenhagen, Canada committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to 620 Mt by 2020. As it stands, we are set to miss this target by a wide margin. In Paris, Canada promised to reduce its emissions 30 per cent below its 2005 levels. We’re making some headway, but it doesn’t look great.

That is why Canada needs a legislated framework to ensure we reduce our greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and do our fair share of the work to keep global temperature rise below 1.5C.

Drawing from the experience of other industrialized countries who are far ahead of Canada when it comes to meaningful climate action, Ecojustice and our partners have published a report mapping out a proposed federal climate accountability framework. A New Canadian Climate Accountability Act provides a roadmap to ensure Canada never misses another climate target.

Canadians look to our elected officials for support and reassurance – we want to know that our future, and our children’s future, is safe and secure. In recent months, we’ve seen the federal government take unprecedented steps to keep the public safe during the pandemic. They have planned, tweaked, and implemented public health strategies to lower the spread of the virus. But why aren’t they doing something similar to tackle the climate emergency, another urgent public health threat?

Imagine if governments in Canada said their aim was to have zero-cases of COVID-19 by the end of 2020 but failed to take immediate action to make that a reality. Rightly, the public would be outraged by a lack of action. But that is what’s happened with successive federal governments attempts to reduce emissions – they set aspirational goals, fail to set out a framework for meeting those targets and end up missing them entirely.

Climate accountability frameworks have had a major impact in other countries. The United Kingdom introduced its Climate Change Act – the first of its kind in the world – in 2008. The U.K. has set five carbon budgets, and has met, or is on track to meet, the first three.

Even individual Canadian provinces have acted on climate accountability legislation – B.C. and Manitoba have passed climate accountability laws and aspects of a similar framework are being tabled in Quebec.

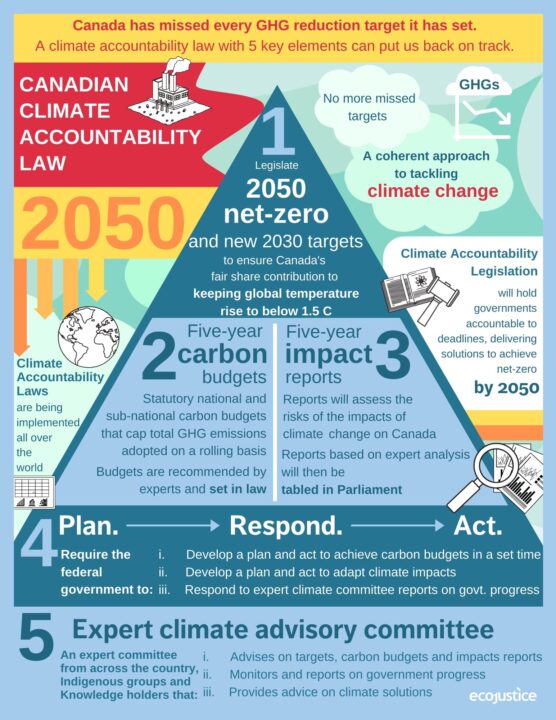

So what is climate accountability legislation based on? In our report we propose five pillars of effective climate accountability legislation:

– Long-term legislated GHG emissions targets for 2030 & 2050

– Five-year national and sub-national carbon budgets, or medium-term targets

– Five-year impact reports which set out the risks climate change poses to Canadians

– An iterative planning & reporting system that mandates plans to meet the targets and adapt to the risks, and reports on our progress on those plans

– An arms-length expert committee comprised of climate change experts, with both advisory and reporting responsibilities

Political promises to “exceed Canada’s 2030 emission reduction goal” and “join countries around the world in reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050” need to be set in law. Legal targets actually commit current and future governments to sustained climate action and signal that commitment to the nation and the world.

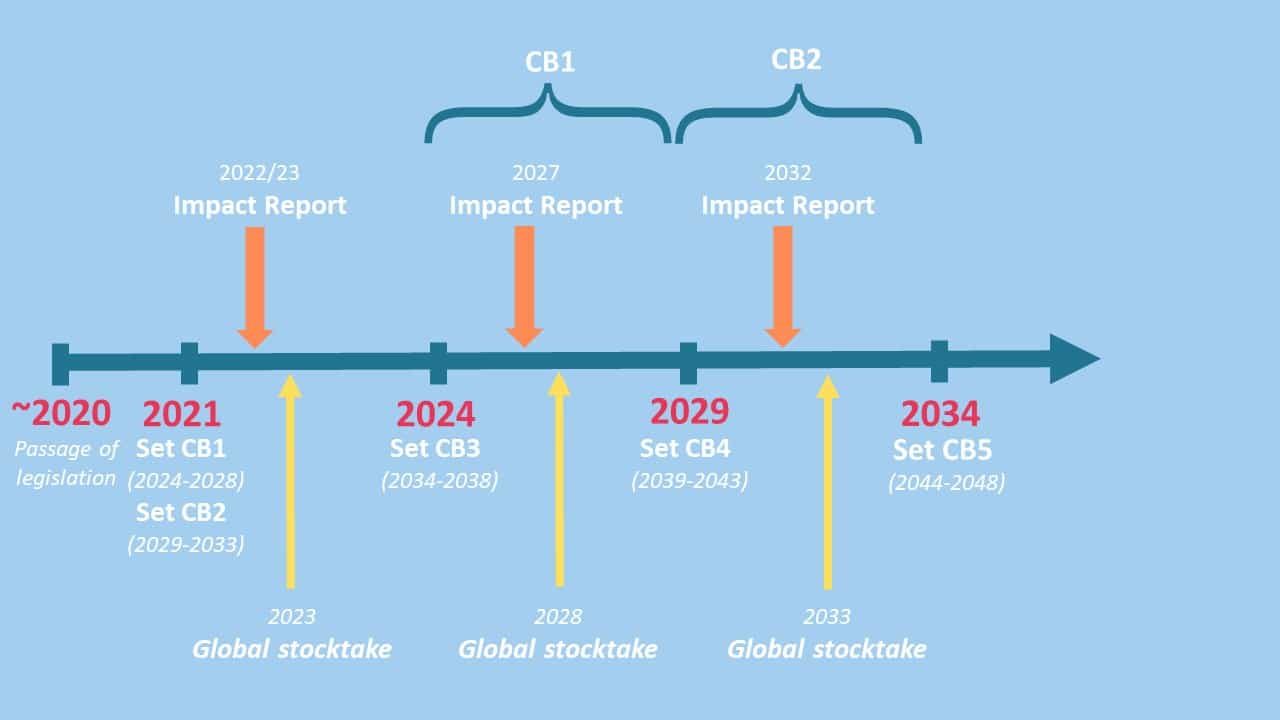

Targets are achieved by setting carbon budgets, also known as emission budgets or milestones, that cap economy-wide GHG emissions over a period of time. These budgets set out the path to achieving the long-term targets, carving up those distant goals into more workable pieces. Given the federal makeup of Canada, we need two types of budgets – national and sub-national budgets. Tackling climate change is the shared responsibility of both the federal and provincial governments. We need all levels of government to work together to lower our emissions, and to be clear about it.

Potential timeline for setting of Canadian carbon budget

And we know that the impacts of the climate crisis are forever evolving – contributing to the stress and anxiety experienced by communities and individuals across Canada. That is why in our report, we recommend that every five years, the ministers responsible table a report on the risk and impacts of climate change on Canada. These reports will give us a picture of how we need to adapt, which the GHG targets and budgets tell us how we need to mitigate.

In order to meet the targets set out in the carbon budget, and to adapt to the risks set out in the impact reports, ministers need to plan what policies and strategies they will implement. Integrating GHG reductions and adaptation with a just recovery strategy can help Canadians thrive while acting on the climate crisis. Similarly, ministers should regularly report on their progress and inform the public on how they are doing.

Finally, we need our elected leaders to listen to the experts, just as they have done during the COVID-19 pandemic. An arm’s length expert advisory committee can play a critical role in guiding politicians and helping them make the most effective choices to address climate change. Regardless of changes in government, experts can keep decision-makers on the right path.

Canada cannot expect other countries to do their part to reduce emissions unless we demonstrate we are taking action at home. To date, that action has been sorely inadequate.

A new Canadian Climate Accountability Act can change that, turning intention into action, and be a keystone in the defence of our future and our children’s futures. Let’s get to work.